What is the main principle of Core Process Psychotherapy?

An in depth article by Erik Passig MA CPP

Core Process Psychotherapy

Introduction

2600 years ago, a seasoned spiritual seeker carried a burning question in his heart and was prepared to walk for hundreds of miles to seek a holy man who could possibly give him an answer. Day and night he walked, yearning for an answer that would satisfy his thirst for the truth.

Still hot from wandering through the heat of Northern India, the wanderer Bahiya of the Bark Garment came upon the object of his long sought desire. The peaceful figure with the shaved head and yellow robes was walking serenely, holding his begging bowl. It was Shakyamuni Buddha going about his daily alms round, begging for food.

Straight away, Bahiya rushed towards him and almost rudely interrupted the Buddha’s alms round. Traditionally, the alms round was always done in silence and, for his efforts, Bahiya was turned away twice. When he requested the Teaching for the third time, the Buddha gazed at him with his famous ‘elephant look’ that communicated his total enlightened presence and full attention. He then uttered the following words:

“Well then, Bahiya, you should train yourself like this: whenever you see a form, simply see; whenever you hear a sound, simply hear; whenever you smell an aroma, simply smell; whenever you taste a flavour, simply taste; whenever you feel a sensation, simply feel; whenever a thought arises, let it be just a thought. Then 'you' will not exist; whenever you do not exist, you will not be found in this world, another world, or in between. That is the end of suffering."

Bahiya understood these words and, by “not clinging, thenceforth released his mind from the cankers,” gaining realization instantly. Bahiya, due to having previously followed a spiritual path and being spiritually receptive, was ready to be introduced to the nature of mind and its universal truth. He completely realised the meaning of this teaching is: to discontinue the illusory sense of self, to switch off one’s dualistic perception, and simply ‘to leave experience as it is’.

In the Dzogchen instructions also, which embody the highest teachings of the Nyingmapa tradition in Tibetan Buddhism, one is encouraged not to change or manipulate mental events or perceptions deliberately and simply to leave them as they are, so that one’s intrinsic pure nature of mind (Rigpa) is laid bare. The great Tibetan Master Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche clarifies this in the following statement: "if you are in an unaltered state, it is Rigpa." If we force or contrive in relation to our experience then this state is not Rigpa. According to the Dzogchen tradition, as meditation deepens, there are the four chokshyak or profound ways of leaving things in their natural simplicity:

View, like a mountain: leave it as it is

Meditation, like the ocean: leave it as it is

Action, appearances: leave them as they are

Fruition, Rigpa: leave it as it is

The instruction on how to work with the mind and its risings is simply to ‘leave it as it is', without grasping or pushing away experience, but at the same time to be completely open, as Dudjom Rinpoche says, to "whatever perceptions arise; you should be like a little child going into beautifully decorated temple: he looks, but grasping does not enter into his perception at all. So you leave everything fresh, natural, vivid and unspoiled. … Whatever appears is unstained by any grasping, so then all that you perceive arises as the naked wisdom of Rigpa, which is the indivisibility of luminosity and emptiness."

If we could remember this, we would be free from suffering. Unfortunately most of us don’t and thus we suffer. Some people approach Buddhism directly seeking release from suffering, while others take the route via psychospiritual therapy.

These teachings are about seeing, recognising and ‘being with’ rather than altering what is. Core Process psychotherapy (CPP) is rooted in Buddhist teachings such as these. One of the unique features of CPP is to come more and more into relationship with one’s experience and to learn how simply to be with it. In this respect this is quite a different approach from the cognitive behavioural therapeutic approaches or the more psychoanalytic interpretive interventions. One does not quickly interpret or devise a better and more efficient behavioural strategy. By merely allowing oneself to be with experience and by just staying with awareness in the present moment, one notices whatever is arising in one’s mind and how it naturally of its own accord passes away.

One does not exclusively bring awareness to one’s own risings, but is also aware of the co-emergent field of awareness, which can be experienced on many different levels between client and therapist.

This is sometimes referred to as ‘joint sitting practice’.

CPPwas developed by Maura and Franklyn Sills over the last 40 years. Major influences in the development of Core Process Psychotherapy include the work of Alexander Lowen, Gestalt therapy, Stan Grof, Bill Swartley, and William Emerson, as well as psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology, and Jungian psychology. These approaches and skills were explored and developed in the context of Buddhist psychology and awareness practice. Therefore, Core Process Psychotherapy is a psycho-spiritual approach to therapy.

In this article aspects of the Buddhist formula of dependent origination in relation to awareness, as well as the core model of personality shaping, will be explored with a particular emphasis on the significance and awareness of the 'felt-sense' (a term derived from Focussing, explained later in this essay). The main current that runs through Core Process Psychotherapy is the belief that awareness in the present is inherently integrative and healing and that this can be explored in relationship. This belief is based on a depth understanding of human personality process and of human potential. In terms of potential, human beings are perceived as essentially free, fundamentally unconditioned, and in their deepest nature boundless pure awareness out of which loving kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and peace (upekkha) naturally arise.

This luminous mind, which Chogyam Trungpa refers to as 'brilliant sanity', originally stems from the Buddha's teaching of tathagatagarbha. The 'Tathagata [Buddha] seed', or Buddha-womb, suggests that there is something implicit in our nature that has the quality or potential of enlightenment somewhere in our mind. In the Anguttara Nikaya, the Buddha says, "This consciousness is luminous, but it is defiled by adventitious defilements." This Buddha-nature or essence of mind is covered up by the defilements of attachment, aversion, and delusion and is therefore yet unrealised. If there were no Buddha-nature or no no-self, there would not be a constantly changing flux of phenomena, but an enormous rigid deterministic machine, devoid of the chance of liberation from suffering.

In the therapeutic context, this means that the therapist does not view the client as a separate fixed personality with a certain bundle of habits that need to be helped or adjusted, but as an ever-changing being with no-self or the open dimension of being at its core. If this inner attitude is present, a great sense of spaciousness and openness can occur, which paves the ground for resonance and healing, a mutual exploration of the client's processes, which helps to dismantle any possible sense of helplessness and stuckness that the client may feel.

Looking at human personality process, we shall now be concerned with the conditioned personality structure, the separate sense of self that is alienated from the process of becoming and constantly takes fixed positions in relation to our experience. Core Process Psychotherapy work is an exploration of how we alienate ourselves from this natural state of awareness. For example, as we are resting in awareness and open-heartedness, we might notice an object or event (internal or external) entering our field of awareness and start to identify with it. Most of the time we instantly react against it, based on past tendencies, out of which feelings arise, followed by a pushing away or grasping of the experience. Through this process, a sense of self is created, thinking it needs defending, and is less open to a present spontaneous response to the moment.

The question arises: what pulls us away from that state of natural awareness? In Buddhist terms, there are the adventitious defilements. One of the main, and probably the main defilement, is a deep 'thirst' (tanha, trsna) or craving that fuels us to want more of what is pleasurable and the desire to avoid what is painful. This passionate greed can manifest in many ways and is categorised into three modes of craving: for sensuous forms, when craving for a particular form arises together with desire for sensuous pleasure; for existence, when it arises in association with a wrong belief in eternal personal existence or theological dogmas such as that of the 'immortality of the soul'; or for non-existence, when it is connected with the false view that personality is annihilated at death.

If we become pulled in by one of those cravings, we lose our sense of spaciousness and awareness. To stay in the gap of awareness allows us to access deeper layers of our experience and not to become overly entangled with our likes and dislikes, which can easily harden into fixed ego positions in relation to our experience and the world. This entanglement is bound to lead to suffering as our desires do not match the way things are.

Everything we hold on to will have to pass away; for example, the partner or lover we dearly love might not love us any more, or dies away, our bodies age and become sick, and we ourselves will die one day. Within conditioned existence, everything is changing all the time. There is no fixed self or entities that are independent and completely separate from the continual flow of transient phenomena that roll on and on. Therefore they are intrinsically devoid of a fixed self nature (the anatman doctrine). All conditioned phenomena are sustained by an interwoven network of conditions and ultimately do not 'stand on their own feet', as everything is constantly mutually penetrating, even though things happen to appear as different as water and ice. No object or person within conditioned existence can grant eternal satisfaction, as they are marked by insubstantiality, impermanence, and, ultimately, unsatisfactoriness. As our object of craving is insubstantial and impermanent, it is unsatisfactory to crave for it, as we are only able to hold onto it for a relatively short while. In addition, the human mind will only be completely satisfied if it has fully realised the transcendental core or pure boundless awareness, which is the source of true satisfaction. Ultimately it is constantly present if we could only realise it.

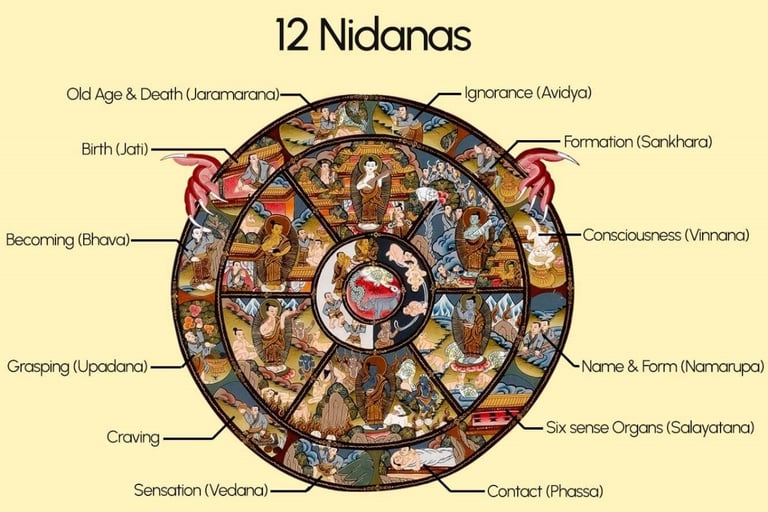

The Buddhist formula of the twelve links (nidanas) of dependent origination of the round describes the cause and effect chain that perpetuates suffering within cyclic existence and which is fuelled by a reactive state of mind. The formula of the twelve nidanas particularly emphasises certain points in the chain where we can break free and dwell in the 'gap of awareness', which disrupts the negative cycle leading to further pain. If we are not in the 'gap of awareness' then, for example, in dependence on feeling (vedana), craving (trsna) arises, which will result in an act of volition which motivates us towards or away from something. We tend to react to pleasant feelings with craving, to neutral feelings with indifference, and unpleasant ones with aversion. Therefore we can never be fully content with what is, since being alive involves pain, and we experience suffering again and again. If we are caught in a reactive mode and feel a painful sensation, we crave for non-pain or pleasure. We tend to respond in a narrow contracted way rather than with a sense of spaciousness that is permeated by a kind awareness.

The seventh link, which is named vedana or feeling, is traditionally illustrated by a man whose eye is pierced by a poisoned arrow. The sensation and feeling that the man experiences are so strong that he is partially blinded. To bring awareness, or not, to what is happening at that crucial point will determine whether one falls into craving, or not. If the gap of awareness is missed, craving arises, which is illustrated by a man drinking, served by a woman, which symbolises that desire is a kind of insatiable thirst. In the case of alcoholic drink, it is easily imagined how it would lead to intoxication. Following from the thirst, attachment, becoming, birth, old age, and death come into being, perpetuating the cyclic or reactive mode of existence.

Feeling is considered the last part of the effect-process of the present life. Provided the process does not verge into craving, no further karma is accumulated, the cycle is finished. Craving is the first part of the cause-process in the present life, leading on to further stages in the chain of the twelve nidanas of the round. According to certain Buddhist teachers, the juncture between the seventh and eighth nidanas is 'the battleground of the spiritual life', and 'to experience feelings, yet check desires, is that victory over oneself which the Buddha declared to be greater than the conquest of a thousand men a thousand times'. We can be hooked by the short term pleasure of distraction, or we can rest in awareness that leads to the cessation of pain, or liberation. This process often involves staying with painful feelings without reacting against them.

The man with an arrow stuck in his eye might painfully remove the arrow from his eye without asking for too long who has shot the arrow or how he could revenge himself. To just bring kind awareness to the painful feelings and sensations is very healing and can transform our lives. In terms of the twelve links (nidanas) of the spiral path which ultimately leads to liberation from suffering, in dependence upon the realisation of the unsatisfactoriness of mundane things (dukkha) or the reactive mode of being, confidence or faith (sraddha) arises. The realisation that we are 'bigger' than our pain and our cravings and that we do not have to hold so tightly to previously dear habits or views, draws us closer to a deeper awareness or even to the core and gives us therefore true confidence. In dependence upon confidence arises joy as our energies are now fuelled by awareness and become freer and freer, which leads us, according to the twelve nidanas of the spiral path, to rapture, calm, bliss, in successive stages, up to the realisation of the 'way things really are'.

There was an occasion in a therapy session when a male, largely built client processed this rage with his father. As this happened, he threw a large black meditation cushion, which was in the room, at me.

Very briefly, a moment of spontaneous awareness, the gap of awareness arose. My hands went up, took the cushion, and I pushed it, and it flew three or four meters into the left side of the room, neatly stacked with the other meditation cushions.

The client was surprised, because I did not react like his father, pushing back some kind of aggression, which would be perceived as an attack. Neither did I take the aggression inside in a victim like manner , but just stayed in the moment of awareness, aiding the healing of his relational wound, whilst holding an open awareness and spacious presence.

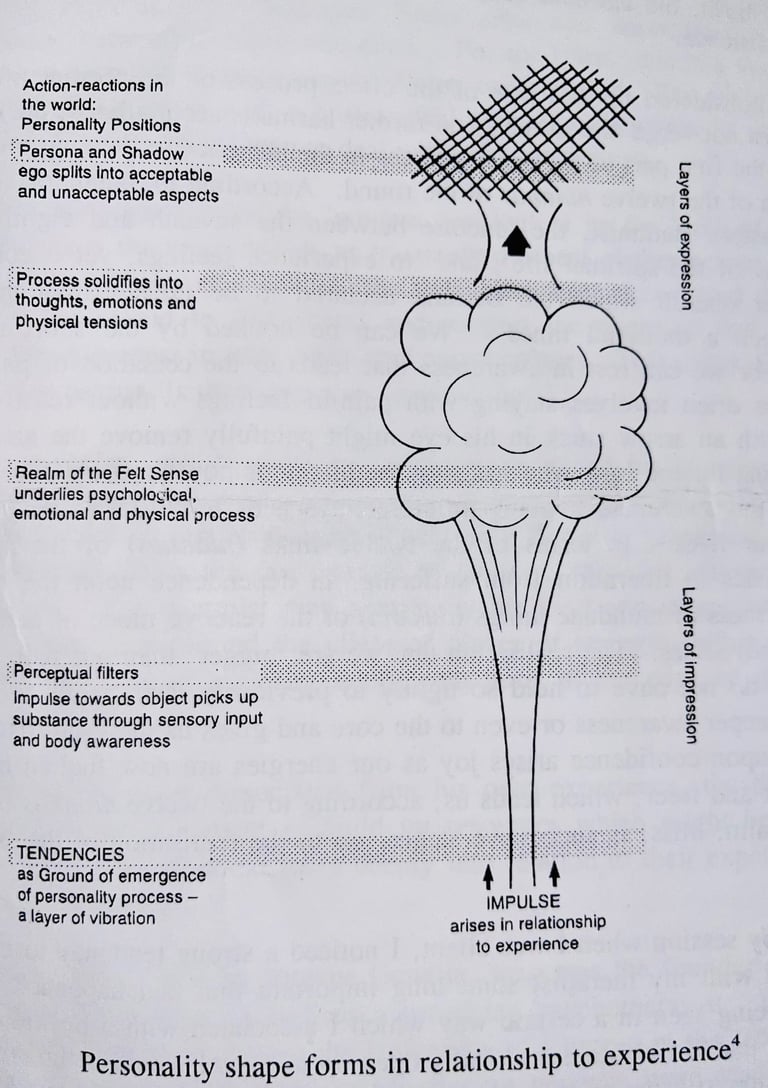

The formulae of the twelve nidanas, which should be taken as a model for conditioned co-production, rather than reality itself, are presented in a very linear, sequential manner and derive from a temporal view of the process of 'becoming' either leading to craving and suffering or to liberation. The Core Process model divides the process of personality shaping, which is the movement from the inherent core state or the open dimension of being towards a sense of separateness, into several layers, emanating from the core. It therefore draws on a more spatial than temporal-linear approach, as, in experiential terms, everything is happening within the present moment. The process of personality shaping in relationship to experience solidifies through several layers of impression (internal events), begins with subtle vibrational tendencies and moves through perceptual filters to the realm of the 'felt-sense' (a subtle realm of feeling before thoughts, emotions or sensations crystallise). Then it is passing through layers of expression into thoughts, emotions and physical tensions which the ego splits into acceptable and unacceptable aspects, similar to Jung's concept of persona and shadow, finally accumulating in actions-reactions in the world, producing personality positions.

When the client is confronted with an unacceptable aspect of themselves or a 'fixed' personality position, it is often very difficult to just be aware of them and to let them go. The experience is so painful that the person either feels the need to dissociate from it or is in danger of suffering overwhelm. The therapist is ideally setting up the best possible conditions for the exploration of whatever issues arise and encourages a 'field of awareness' to emerge between therapist and client. For the client, this is a very valuable resource in itself and seems to be conducive to deeper experiencing. The client might feel safer to explore the given issues with a professional person, with whom he or she has a positive trusting relationship, rather than to deal with it by themselves.

The therapist might temporarily hold the 'witness position' or be the 'pole of awareness' whilst the client explores the unacceptable or traumatised aspect of themselves. When the client encounters very difficult experiences, the skilful therapist can remind the client of their resources (or be of aid to find them) and support the client to find a sense of spaciousness and expansiveness in very contracted narrow places. This could, for example, be invoked by simply asking 'Is there any space around that?'

In the case of overwhelm, the therapist may support the client by 'slowing down' the client's flux of experience by encouraging the client's awareness to stay with a particular relevant physical sensation or just by frequently enquiring 'What is happening now?' This awareness seems to slow down the fast cascade of feelings, thoughts and sensations that occurs in overwhelm. The therapist may simply by his kind and aware presence be a strong resource in itself and remind the client of places of strength within himself and encourage a continual sense of curiosity whilst remaining at the edge of the traumatic experience with awareness.

If the client seems to be quite dissociated from his own experience, the therapist may gently help and encourage the client to build up resources which might be tangible or imagined, so that he or she can come more deeply into relation to their experience within the body or even the 'felt-sense'.

The term 'felt-sense' was coined by Eugene Gendlin, who was the founder of Focussing and is a professor of psychology as well as a practising psychotherapist. In a piece of research into psychotherapy conducted at the University of Chicago in the 1950s and early 1960s in which large numbers of taped psychotherapy sessions were studied, Gendlin discovered that clients, irrespective of therapeutic approach, who were able to be aware of their actual, bodily-felt experiences of life situations, made much more successful changes than clients who did not seem to possess that ability. Gendlin developed Focussing, a method which helps to develop this function, which he does not view as a therapy in itself.

Focussing is a way of self-reflective experience of creative changes from an inner awareness which is located in the body. The central concept is that the body can be used as a sense organ by bringing attention inwards to the felt-sense, which is described as an inner sensing which is unlike our five outer senses or physical sensations (e.g. stomach tension). It is not a 'gut feeling' either, yet it is the inner place from which emotions, new meaning and insights emerge. The initially unclear body-sense moves to a 'felt shift' which brings relief and clarity and can lead to new and unexpected possibilities, overcomes fears, and enhances creative activities. Learning how to approach vulnerable and sensitive places within oneself with acceptance helps one to be able to deal with suffering and to pass through it.

This connected bodily-centred experiencing can be learned and practised by anyone. Focussing, as well as in Core Process Psychotherapy, the therapist creates a space where inner processes are encouraged, e.g. through (a) 'experiential listening' and paraphrasing, which entails reflecting the client's experience rather than giving interpretation or rationalised understanding of it, and (b) making suggestions or asking questions to help the client to find the felt-sense, rather than allowing distraction by the intellect; such a suggestion could be 'See if you can find how this whole thing feels in your body'.

The felt-sense layer is less defined than emotions, which are more intense and will come object-related or personality based. The felt-sense is closer to the unformed, less shaped process of becoming and is nearer to the very basic push and pull dynamic or vedana (as explored in the twelve nidana chain of the round). In the core model, this layer is closer to the unconditioned or pure awareness. To be at this edge of awareness builds a bridge between the usual conscious person and the deep universal reaches of human nature, where we are no longer ourselves. It is open to what comes from those universals, but it feels like 'really me'.

To be with the felt-sense allows us to 'loosen up' and dwell in the realm where less of a fixed self is present. We are closer to the unknown and if we can give our judgmental commentaries a rest we come closer and closer into contact with 'what is'. This requires a great amount of trust and courage as real change can happen in this layer of experience.

To practise therapy within a psychospiritual context is a very beneficial support for this work. We learn to allow the therapist to hold the pole of awareness and learn more and more to bring awareness unconditionally to our own process, may it seem boring, joyous or agonising. The skill of focussing can be taught and learnt in a formal method of several steps, yet as it is an essential life skill it seems very important to me that we aim to live from that place in everyday life, not only in a formal therapeutic situation, but more and more of the time.

We now have explored the 'gap' of awareness between feeling and craving within the context of the formula of dependent origination, as well as aspects of the Core and the core model of personality shaping, with a particular emphasis on the felt-sense layer, although we have really only scratched the tip of a large iceberg. For me, core process work is to learn how to truly trust that deep inner current of awareness that moves us to healing and completeness and how we can experience this in relationship.